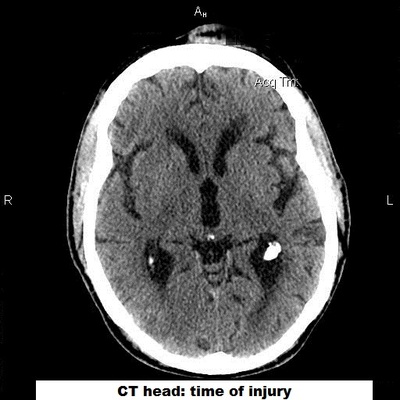

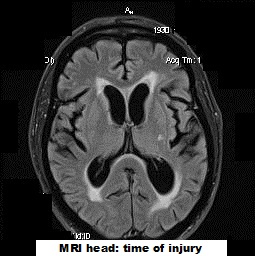

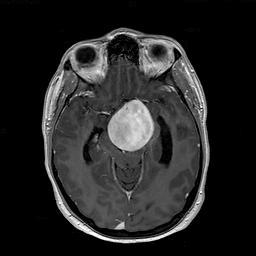

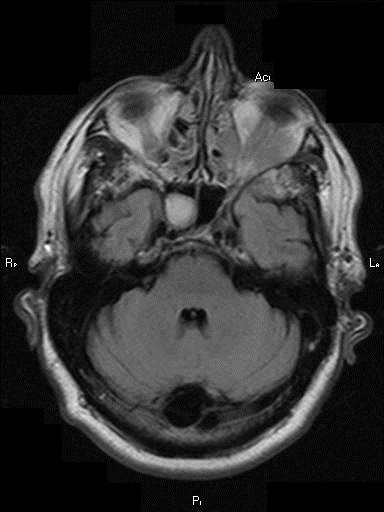

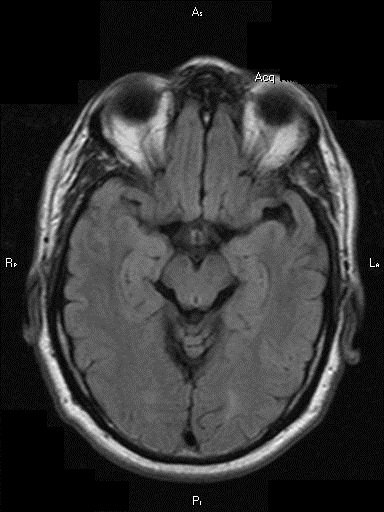

First, an MRI of the brain showed signs that cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was pushing into the adjacent brain (‘transependymal flow’). In addition, when comparing the size of the ventricles (the chambers found in the center of the brain that house the CSF) to the size of the ventricles from a pre-accident MRI, it was clear that the ventricles were much larger. This suggested that he had acquired hydrocephalus (‘water on the brain’).

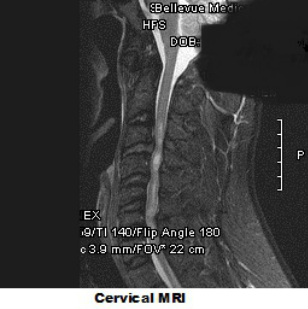

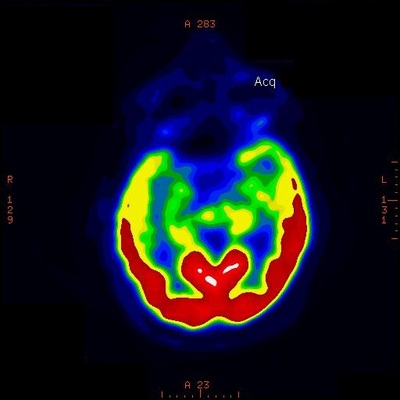

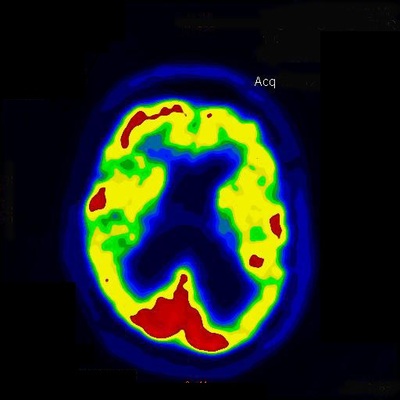

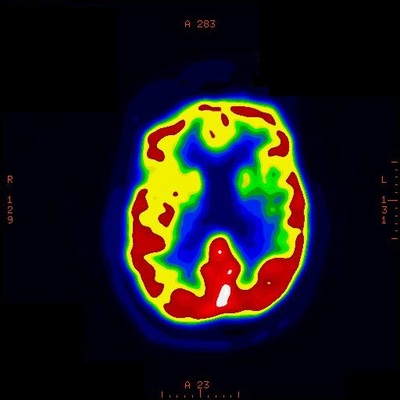

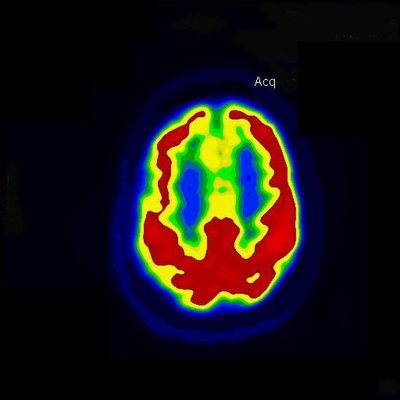

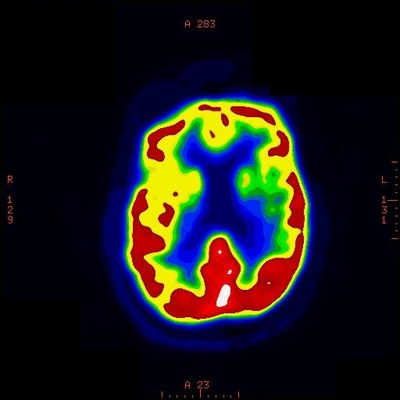

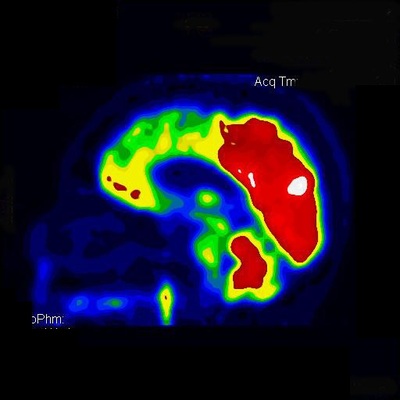

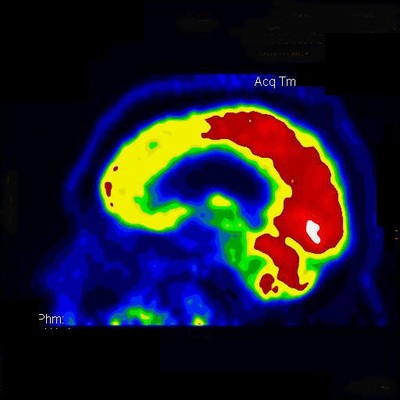

I then sent him for a lumbar puncture which revealed a normal pressure when performed – rather than an elevated pressure as one might expect. I then performed a nuclear study called an Indium-111 cisternogram in which radioactive Indium-111 is injected into the CSF around the lumbar spinal cord. In a normal person, this Indium-111 will not collect inside the ventricles but with patients who have a condition called Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (NPH), the Indium-111 does end up inside the lateral ventricles. This test was positive for this patient.

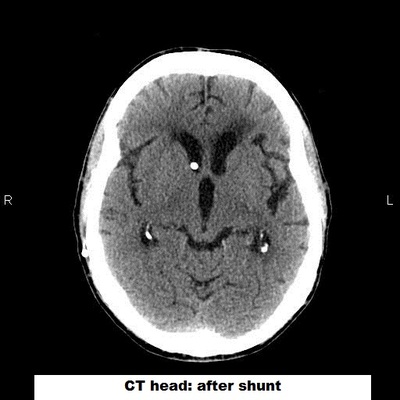

He underwent placement of a ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt and immediately showed a return to his normal walking pattern and had resolution of his urinary urgency. The confusion improved as well.

Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus is thought to occur as a result of blockage of arachnoid granulations by degraded blood products. Normally, the arachnoid granulations are responsible for resorption of the used CSF. If an individual has experienced an intracranial bleed then they are theoretically at risk for developing NPH afterwards. The classic clinical triad is ‘wild, wet and wobbly’ meaning worsening cognition, change in urinary habits and change in gait. The treatment is placement of a VP shunt which will drain a small amount of the CSF continuously into the person’s gut.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed